There are

lots of things related to preparing to give instruction whether for a few hours

or days. This is only about the easier

element – calculating the costs.

Costs – these are both variable and fixed

costs. These are important in calculating

costs per student.

Variable costs. These are the expenses you have no

matter how many may attend. E.g.:

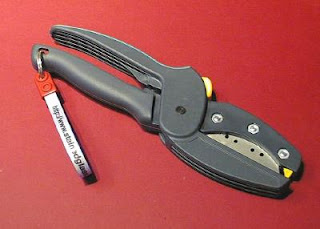

Tools – how many people do you intend to

cater for? What kind of tools do you

need? Does each person need the tool all the time, or can some doubling up occur?

Advertising, promotion – The costs in printing and time to

distribute leaflets and other promotional efforts. Costs of advertising online or in print.

Course Preparation and

delivery time – Every

course requires time to plan the course and organise the materials, take

bookings, set up at the venue., etc. The amount of

time you spend delivering the course/class needs to be added/claimed.

Travel expenses and

time to get to the

venue. Mileage expenses only cover the

transport costs, it does not include your time.

Venue costs – If you have been invited, check

the venue is free to you. In some cases,

you will have to pay for the venue and this needs to be added to your variable

costs. In this case, I am assuming the

host is providing the venue free. If it is

your own venue, you should add a sum to cover the overheads of your premises at

the very least.

Variable costs. These are the costs for each person

on the class/course.

Materials and consumables - The materials the students will

use varies directly with the number of people.

Any provision of food, refreshments will depend on the number. Any handouts or demonstration materials are

also related to the number of people.

Price.

The price of the course/class will depend on the costs and the profit

you wish to have as well as what the market will stand.

Working out the Costs

I will go

through the main areas of costs and give examples to demonstrate. Not all these areas will apply. When they don’t the cost is zero.

Fixed Costs

Equipment

You can

estimate the number of classes over which the tools and any other equipment will

last.

Example

- Say, you plan on 6 students and the cost of the tools for that many will cost 440.00 and

- you expect the tools to last for 10 courses. (you will have to top up on tools due to loss during that period, so you may want to add an additional sum to your calculations.) Ten classes of 6 gives you 60 people to spread the cost across.

- This gives you an individual cost of 7.34 on this basis.

Cost sub total: 7.34/student

Promotion and administration

The

promotional effort includes time to prepare, costs to produce and time to

distribute. You can prepare the

advertising before the pricing begins, so that amount of time can be known

before you start. The costs of printing

or publishing can be determined by getting estimates. The amount of time you spend in distributing

leaflets, and in using the internet to advertise needs to be included in the

promotional time.

I am going

to assume your administration of the applications and payments for the course

are taken by the venue. If you do them,

you need to add a notional amount of time to cover that aspect of delivering a

course.

Example

- Assume the printing and advertising is going to be limited to 50.00. In addition, you are going to spend 5 hours distributing the printed leaflets and 10 hours of social media time promoting the classes.

- As you can see, your time is going to be a large part of this promotional work, so this is the occasion you must decide how much you are going to pay yourself. There are ways to do this. Here is one.

- Say you have decided that you need to pay yourself 20.00 per hour. This is the figure that needs to be applied to all the time-based costs you incur in preparing and delivering the class.

- The promotional costs for the course are going to be 50.00 plus the 15 hours (distributing leaflets and 10 hours social media) at 20.00 (=300.00) totalling 350.00.

- Will this promotion be useful for subsequent classes? Probably not. This means that you can’t spread the cost over more than one course unless you redesign the materials in some way. It may be that subsequent classes will require less effort to promote them, but don’t count on it.

- Assume your promotion cannot be spread over more than one course, which is the most likely. This means the cost for each of the six people is 58.34

Cumulative cost sub total: 65.68/student

Preparation

You need to

prepare a course syllabus or outline at least.

This will guide you in the presentation of the class and will help you

determine the equipment and materials your students will need. Any additional materials and equipment needed

for the course will need to be added to your initial equipment calculations. You need to keep track of the amount of time

you spend on designing the course.

Example

- Assume 10 hours researching and writing your course.

- You can decide that little alteration of the course will be required over the life of the equipment. This then becomes 200.00 divided by 60 students or 3.34 per student.

- You may also have course handouts. These will be fixed costs as they relate to each student.

Cumulative cost sub total: 69.02/student

Some of

these promotional and preparation costs will have to be guesses until

experience is gained. How long will the advertising last? One class or more?

Will you need additional preparation time each time the class is held? The answers you give will affect the

calculations by the number of students or classes the cost is distributed.

Travel and accommodation

Of course,

The travel expenses and time, and the class delivery time will remain relatively

constant; varied only by the distance and the facilities at the venue.

Example

- The venue is 25 miles away.

- The travel time is 45 minutes each way.

- The set-up time is 30 minutes. The course is for 4 hours and clean-up is 30 minutes.

- This means that at 0.50 per mile the expense is 25.00; t

- he travel time is 1.5 hours (1.5*20.00) gives an expense of 30.00 to get to and from the venue.

- Set-up and clean-up is 20.00.

- Class delivery time of 4 hours equals 80.00.

- All these on the day costs are 155.00. For six students, this will be a cost of 25.83 each.

Cumulative variable cost sub total:

94.85/student

Of course, your accommodation expenses for a multiple day

course will need to be added, although not the time between class sessions.

Fixed costs

these are the ones directly related to

each student. These will vary according

to venue, style, length etc.

Materials/consumables.

The materials the students will use

varies directly with the number of people.

The costs of this relate to the materials the students will consume

during the class/course.

Example

- The glass used by each student will cost 20.00

- Additional consumables will be 10.00

- Firings for each student will be 5.00

fixed cost sub total: 35.00/student

Hospitality - provision of food, refreshments - will

depend on the number.

Example

- Refreshments at the beginning and middle of the course 5.00 each

fixed cost sub total: 40.00/student

Any handouts or demonstration materials are also

related to the number of people.

Example

- Handouts and examples for students – 10.00

fixed cost sub total:

50.00/student

Student accommodation – this is relevant for those who

need to stay overnight either because of their travel or the length of the

course. Normally, this is the

responsibility of the student. It may be

that you wish to include the cost of this in the course fee, although that

usually makes the course appear to be very expensive. In this case, I will assume accommodation is

the responsibility of the student.

Cumulative variable cost sub total: 94.85/student

Cumulative fixed cost sub total: 50.00/student

Total cost for a one-day, six-person class: 144.85/per student

Profit

You do need

to make a profit on this class, or you can’t continue. You can’t continue with an “at cost” basis,

because this is time away from making where you can generate an income. A small profit margin of 20% is the minimum.

It does give you some recompense for your knowledge and provides a small margin

for contingencies.

Example.

A margin of 20% on the above example would add 28.97 per

student.

Cumulative cost total: 173.82/student

If you feel

this does not represent good value for your experience and knowledge, increase

the price. This exercise only provides the

base cost level for setting the price.

Also remember that it is easier to reduce prices than it is to increase

them.

On the other

hand, you may decide that your hourly charges are sufficient profit for the

course. This is not advisable, but is a

choice you can make. You should always

be aiming for doing your work on a cost, plus profit basis. Not simply covering material costs and

expenses. Remember your time is also a cost factor.

If you were

to feel this is too expensive, there are some ways to reduce expenditure. The

only ones that you cannot reduce are your hourly rate and the profit margin.

Possible reductions include:

Tools and equipment – get the venue to share costs or underwrite

costs.

Promotion – reduce your expenditure, or get the venue to take

all or most of the promotion costs.

Venue – get them to set-up and clean-up, or better, get the

students to do these things. Get travel

expenses from the venue. Move the venue

closer.

Accommodation – get the venue to provide at their cost.

Student numbers – get more students which will reduce the

variable cost per student.

But – to repeat – do not reduce your

hourly rate, ever.

This is a

general introduction to costing, profit, and pricing. There are a lot of more sophisticated ways of

calculating these things, but until a lot of experience is gained, most of the

work will be from estimates and guesses.

So, investing in highly detailed methods will not make the pricing more

accurate, as all the calculations are based on estimates.