This is a presentation I gave a while ago on why and how to test for stress without risking the piece, that is, non-destructive testing.

Wednesday, 21 January 2026

Stress Testing - How?

This is a presentation I gave a while ago on why and how to test for stress without risking the piece, that is, non-destructive testing.

Wednesday, 8 October 2025

How Can I Relieve Stress in Fused Glass?

|

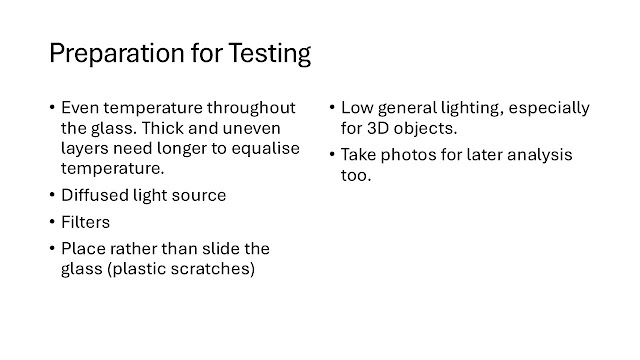

| An stress test strip and annealing witness between polarised filters. |

If an unbroken fired piece shows stress that is known not to be from incompatibility, it is possible to fire and anneal again to relieve the stress. If the stress results from incompatibilities, annealing again will not change the compatibility. The process for stress testing is here.

Conditions for doing this re-firing are:

Slower heat up rates than usual for this thickness and profile are required. The glass is more than usually fragile and needs gradual heating. This avoids creating additional stress that may cause a break.

Take the temperature up to the lower end of slumping temperature range - say 600 - 620C (1100 - 1150F) - and soak for 10 – 30 minutes depending on profile and thickness. This ensures any existing stress is relieved and the glass is ready for the annealing.

Reduce the temperature as fast as possible to the existing or new annealing temperature.

Anneal for longer than previously. This can be for a greater thicknesses than the thickness and profile used for the stressed piece. Most importantly, the anneal soak for the combination of profile and thickness needs to be followed.

My experimentation has shown that the profile determines the additional amount of thickness that needs to be allowed for a sound anneal is as follows:

- Full flat fuse - fire for the thickness (i.e. times 1)

- Contour fuse - fire for 1.5 times the thickest part

- Rounded tack fuse - fire for 2 times the thickest part

- Sharp tack/sinter - fire for 2.5 times the thickest part.

Use the cool rates related to the anneal soak time. These are available from the Bullseye site for Celsius and Fahrenheit. Too rapid a cool can induce temporary stress from differential contraction of the glass that is great enough to cause breaks, so follow the rates determined for this thickness and profile.

These rates are scientifically determined for all glass and especially for fusing glass and are inversely related to the anneal soak. That means the longer the anneal soak, the slower the cooling rates need to be, and directly related to the soak length. It does not matter which manufacturer's glass is being used, all the target times and temperatures should be followed, except the annealing temperature.

More information is available in my e-book Annealing Concepts, Principles, and Practice available from Bullseye, Etsy, and stephen.richard43@gmail.com