From the Mo-Sci Corporation Blog:

Posted by

While historically a source of problems for glass producers, the phenomenon of phase separation is now known to offer advantages in the production of certain materials such as glass ceramics and porous glasses. Whether desirable or undesirable, understanding and controlling phase separation during the glass manufacturing process is crucial. In this article, we explore the basics of phase separation and how it can be manipulated to create advanced materials for various applications.

What is phase separation?

In physics and chemistry, the word “phase” refers to a region of a material that is chemically uniform and physically distinct. Phase separation, which typically occurs in liquids, is where a homogeneous mixture separates into two or more of these phases. For example, a mixture of water and oil at room temperature will naturally “phase separate” into a distinct phase consisting of pure oil, and another consisting of pure water. We can say that such a mixture is “immiscible.”

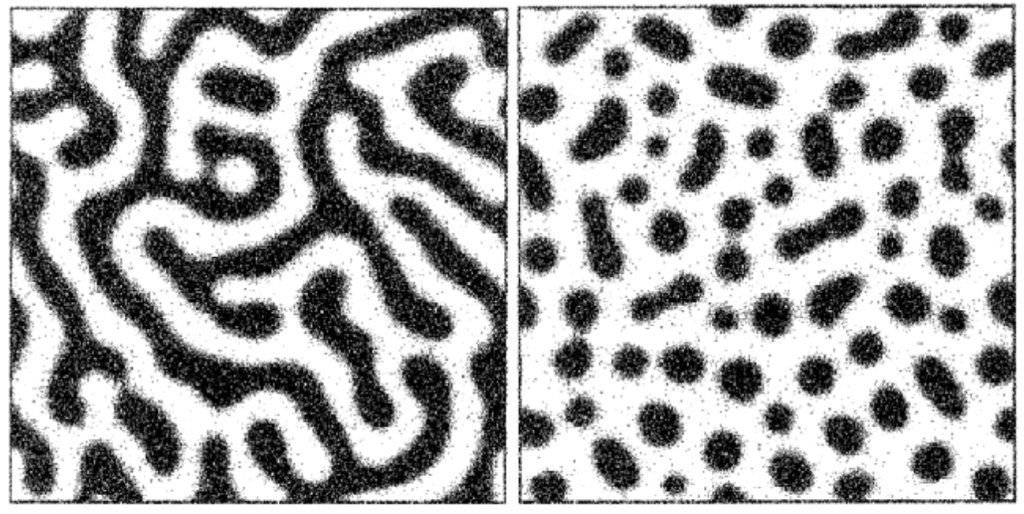

The morphology of this phase separation can vary depending on the relative concentration of both components. If the mixture is predominantly water, the oil phase will take the form of distinct (or “discontinuous”) droplets dispersed throughout an interconnected (or “continuous”) water phase. If the mixture is predominantly oil, the opposite will take place. At roughly equal proportions of oil and water, each phase will tend to be continuous.

Phase Separation in Glass

Phase separation commonly occurs in glass melts. Borosilicate glass – which contains both silica and borate as network formers – is a well-studied example.1,2

Unlike our water/oil example, phases in glass melts are not necessarily chemically pure. Borosilicate glass, for example, will typically undergo phase separation into a “borate-rich” phase and a “silica-rich” phase, with both phases containing different proportions of each network former. In addition, the morphology of separated phases in glass can vary. While it is possible for droplet-like phases to form via classical nucleation and growth, spontaneous “spinodal” phase separation can result in the formation of intertwined tendril-like continuous phases.3

This phase separation, which occurs at high temperatures in the molten glass, persists and “freezes in” when the glass is cooled into a solid. If both phases are vitrifiable, they may form glasses after cooling (this is called a glass-glass phase separation). However, if one phase is prone to crystallization, the mixture can cool into a glass-crystal phase-separated solid.5

Phase separation in glasses was long seen as undesirable – and for many applications, it still is.6 The existence of different phases modifies the physico-chemical properties of glass melts, making it difficult to mold and reduce the quality of the final glass.

The physics of phase separation in glass-forming materials is complex, and even today the specifics are subject to intense debate.7 However, glass manufacturers nonetheless determined ways of avoiding or minimizing phase separation during glass manufacturing.

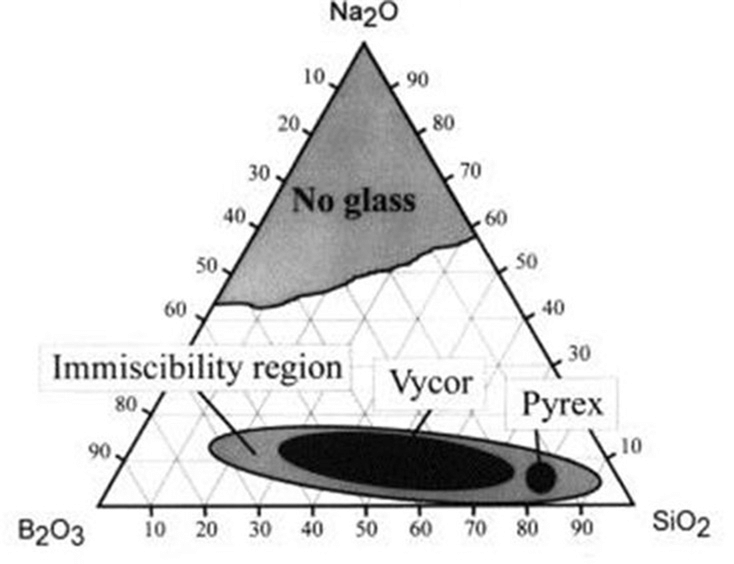

Typically, this is achieved by tailoring the composition of glass melts, with phase separation only occurring for specific compositions. In a Na2O–B2O3–SiO2 glass system, for example, the following ternary phase diagram shows the immiscibility region in which phase separation will occur.

Phase separation (and subsequent crystallization) can also be controlled by the addition of glass modifiers, and by varying heat treatment and cooling rates.9

Controlling and Exploiting Phase Separation in Glass

Note that within the immiscibility region in the diagram above, two common commercial glass compositions are labeled. Indeed, it’s now understood that phase separation offers advantages in certain applications. Today, heterogeneous phase-separated glasses cover a broad range of commercial applications, including Pyrex®, Vycor® opal glass, porous glass, and glass ceramics.

Glass-ceramics are a class of polycrystalline materials that share many properties with both glasses and ceramics, ideally providing the moldability of glasses with various special properties (such as high strength) of ceramics. Glass-ceramics are produced by the formation of crystal phases within an amorphous base glass (i.e., crystal-glass phase separation). Engineering glass-ceramics depends on controlling crystallization within the base material.10

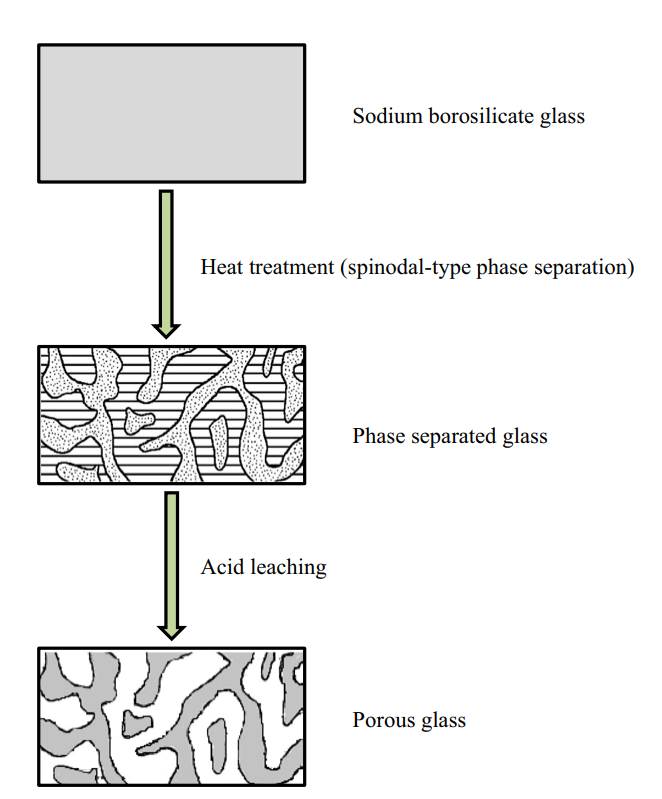

Another application of controlled phase separation is in the production of porous glasses. Porous glasses are typically high-silica glasses that contain pores with a specific size distribution, ranging from angstrom to millimeter scales. Porous glasses are commonly produced from phase separation of alkali borosilicate glass, in which the mixture undergoes spinodal phase separation following heat treatment to yield two continuous phases.11 Following phase separation, the alkali-rich borate phase can be dissolved in acid and removed from the solid. This leaves a highly pure and porous silica glass “skeleton.”

Porous glass exhibits improved mechanical and thermal stability compared to ordinary bulk glass, making it a popular alternative to fused quartz which is comparatively difficult to form. Other applications make use of the pores themselves: such as filitering materials, catalyst supports, and targeted drug delivery.12–16 Mo-Sci is a world-leading provider of advanced glasses for healthcare, electronics and engineering applications. We offer a range of glass-ceramic seals and porous glass solutions, as well as providing custom solutions for virtually any glass application. Contact us for more information.

References and Further Reading

- Charles, R. J. Phase Separation in Borosilicate Glasses. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 47, 559–563 (1964).

- Möncke, D., Ehrt, D. & Kamitsos, E. Spectroscopic study of manganese-containing borate and borosilicate glasses: Cluster formation and phase separation. Physics and Chemistry of Glasses – European Journal of Glass Science and Technology Part B 54, 42–51 (2013).

- Bergeron, C. G. & Risbud, S. H. Introduction to Phase Equilibria in Ceramics. (American Ceramic Society, 1984).

- Gebauer, D., Kellermeier, M., Gale, J., Bergström, L. & Cölfen, H. Pre-nucleation clusters as solute precursors in crystallisation. Chemical Society reviews 43, 2348–2371 (2014).

- Schuller, S. Phase separation in glass. (2018).

- Morey, G. W. The Properties of Glass. (Books on Demand, 1954).

- Da Vela, S. et al. Interplay between Glass Formation and Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation Revealed by the Scattering Invariant. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 7273–7278 (2020).

- Bartl, M. H., Gatterer, K., Fritzer, H. P. & Arafa, S. Investigation of phase separation in Nd3+ doped ternary sodium borosilicate glasses by optical spectroscopy. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 57, 1991–1999 (2001).

- Liu, S., Zhang, Y. & Yue, Y. Effect of cooling rate on crystallization in an aluminophosphosilicate melt. Physics and Chemistry of Glasses – European Journal of Glass Science and Technology Part B 52, (2011).

- Control of nucleation in glass ceramics | Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsta.2002.1152.

- Hasanuzzaman, M., Rafferty, A., Sajjia, M. & Olabi, A.-G. Production and Treatment of Porous Glass Materials for Advanced Usage. in Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering (Elsevier, 2016). doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-803581-8.03999-0.

- Hammel, J. J. & Allersma, T. United States Patent | Thermally stable and crush resistant microporous glass catalyst supports and methods of making. 341–341 (1975).

- Jungbauer, A. Chromatographic media for bioseparation. Journal of Chromatography A 1065, 3–12 (2005).

- Sotomayor, P. T. et al. Construction and evaluation of an optical pH sensor based on polyaniline-porous Vycor glass nanocomposite. in Sensors and Actuators, B: Chemical vol. 74 157–162 (2001).

- Takahashi, T., Yanagimoto, Y., Matsuoka, T. & Kai, T. Hydrogenation activity of benzenes on nickel catalysts supported on porous glass prepared from borosilicate glass with small amounts of metal oxides. Microporous Materials 6, 189–194 (1996).

- Using Porous Glass Microspheres for Targeted Drug Delivery Mo-Sci Corporation. https://mo-sci.com/porous-glass-microsphers-targeted-drug-delivery/.