The use of glass in bone grafts.

|

| image credit: Mo-Sci, Llc |

Posted Krista Grayson on Feb 13, 2019

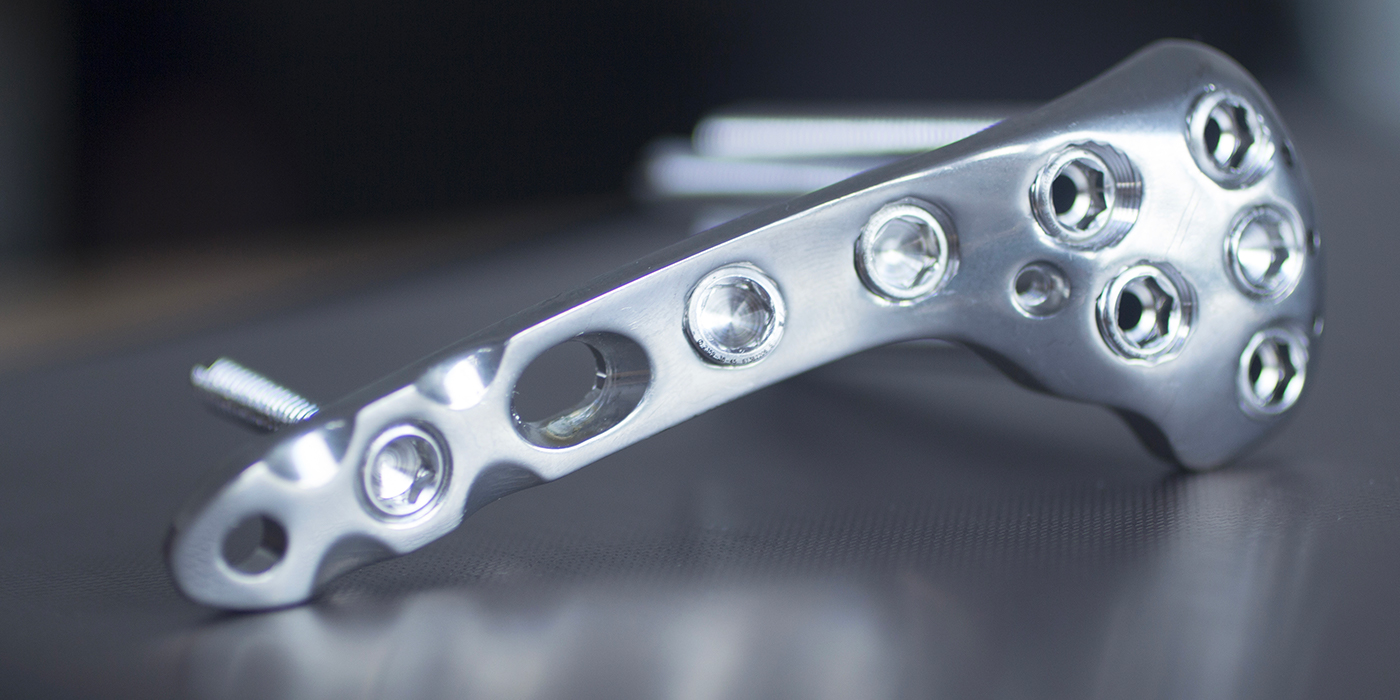

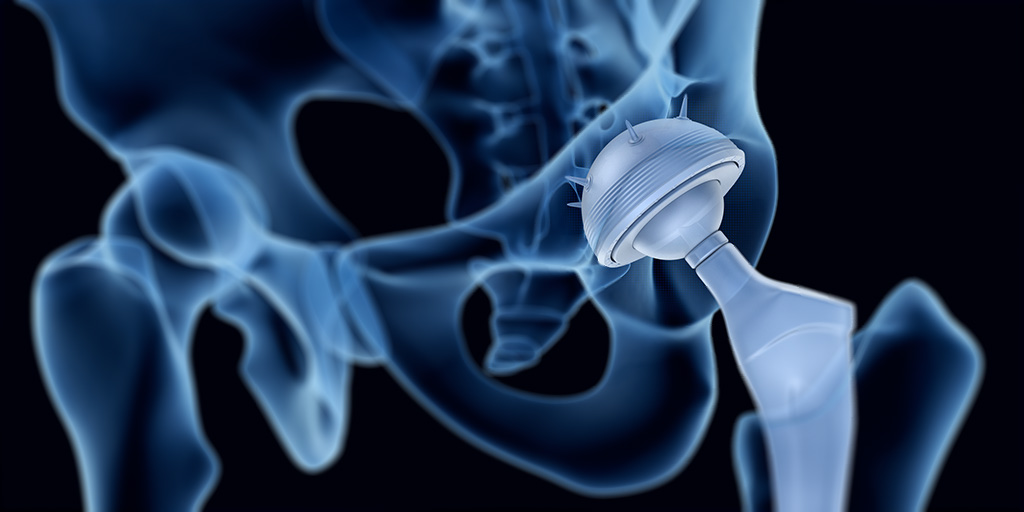

Disease, trauma or serious infection may result in extensive bone damage or bone loss which exceeds the body’s capacity to repair itself. In such cases, implants are needed to promote satisfactory healing. These may take the form of screws, plates, or rods to immobilize broken bones in the correct alignment, reinforce weak bones or correct skeletal deformities. Similarly, diseased joints can be replaced with prosthetic joints to restore normal, pain-free movement.

Despite ongoing medical advances and improvements in materials and procedures, there remains a substantial risk of implanted devices becoming infected. In addition to microbes being introduced into the body during surgery, there is the risk of bacteria transported in the blood from other parts of the body colonizing the surface of an implant. It has been estimated that as many as 2.5% of primary hip and knee replacements and to 10% of joint revision surgeries are complicated by infection.1 Infected implanted devices represent a significant clinical challenge. Typically, despite lengthy antibiotic treatments, it is often necessary for the infected implant to be surgically removed. This not only increases patient morbidity and dissatisfaction, but is also associated with substantial cost.2

Antibiotics continue to be the mainstay strategy for both the prevention and treatment of implant infections. However, the power of antibiotics in the fight against infection is diminishing as many strains of potent bacteria are developing resistance to even the strongest antibiotics. Consequently, the risk of implanted devices becoming infected is on the rise and researchers are investigating novel ways to reduce such infections.

One strategy is based on the discovery that the majority of bacteria live in surface-bound microbial communities, rather than as free-swimming entities. On binding to the surface, bacteria secrete adhesion proteins that provide an irreversible attachment.3 Such bacterial biofilms account for over 80% of clinical microbial infections.2 It was therefore proposed that making the surface of implants unsuitable for bacterial colonization would dramatically lower infection rates. This can be achieved by coating the implant with bioactive glass.

Bioactive glass is a type of glass made from high-purity chemicals, such as silica, calcium, and boron, which induce specific biological activity.4 Bioactive glass, by virtue of its high strength, low weight and biocompatibility, has been widely used in a range of biomedical applications, including tissue engineering, bone grafting, dental reconstruction and wound healing.5

Such clinical experience has shown that borate bioactive glass possesses antimicrobial properties against a wide range of bacteria, including MRSA and E-coli.6,7 The antimicrobial efficacy is achieved though an increase in pH of the surrounding body fluids (which is stressful for bacteria) and because any bacteria that do approach are unable to adhere to bioactive glass and so cannot create microfilms on its surface.8,9 In vitro studies have confirmed that bioactive glass has strong anti-staphylococcal and anti-streptococcal activity.10,11

Since the antimicrobial action of bioactive glass arises from it creating an environment that is hostile to bacteria rather than requiring direct contact with the invading microbe in order to kill it, it is effective across a wide range of bacteria. Furthermore, the bacteria cannot adapt to such effects, and so no bacteria have been found to develop resistance to the antimicrobial effects of bioactive glass.9

Initial technical challenges have been overcome and a range of titanium implants have been successfully coated with bioactive glass.12 Clinical use of implants coated with bioactive glass has given promising results in both orthopedic and dental applications. There was no evidence of the coated implants causing any adverse effects or inflammatory response in the surrounding tissue. Furthermore, the implants coated with bioactive glass were found to accelerate cell attachment and mineralization of the extracellular matrix, promoting more rapid bone growth. In addition, the proportion of bone-to-implant contact was significantly greater for implants coated with bioactive glass compared with traditional implants.13-15

Bioactive glass has good antimicrobial action, being effective against a broad spectrum of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.9 However, the antimicrobial effects can be further enhanced to increase the range of antimicrobial activity, by the addition of ions, such as boron, copper, silver, yttrium, and iodine, or organic nanoparticles.16,17 The chosen antimicrobial agent is incorporated into the bioactive glass during its production and released once the bioactive glass is in an aqueous solution, creating an environment inhospitable for microbial life. The bioactive glass can thus be used as a delivery system for antimicrobials.18

The advantage of ions and nanoparticles over antibiotics is that their efficacy depends solely on contact with the bacterial cell wall; they do not need to enter the cell. Consequently, their lethal effect is delivered irrespective of the specific genetics of the target bacteria and is unaffected by the resistance mechanisms used by bacteria to evade antibiotics.

Infection of medical implants is an increasingly serious clinical and socioeconomic burden. Furthermore, the situation is likely to worsen with the increasing prevalence of bacteria with multi-drug resistance.

Bioactive glass has inherent antimicrobial activity and does not elicit a toxic response to surrounding tissues. Consequently, coating implants with bioactive glass represents an attractive option for reducing the risk of infection. The antimicrobial properties of bioactive glass can be further enhanced by loading it with antimicrobial agents, such as ions or antibacterial nanoparticles. Such a strategy would reduce the need for prophylactic antibiotic use, whereby protecting against the development of further strains of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Since bacteria cannot adapt to the hostile environment created by bioactive glass or its biofilm-resistant surface, they are unlikely to develop resistance to the antimicrobial action of bioactive glass.

In addition, the coating of implants with bioactive glass has been shown to speed up the fusion of the implant with bone, accelerating a patient’s recovery.

The use of bioactive glass, either alone or doped with antimicrobial agents, as a coating for orthopedic and dental implants is thus likely to improve the success rate and enhance patient outcomes across a range of reparative and restorative surgeries by promoting rapid healing and minimizing the occurrence of infection.

Mo-Sci produces high quality bioactive glass powders, the precise composition of which can be tailored to meet specific requirements. They produce bioactive glass suitable for coating orthopedic and dental implants.

Posted Krista Grayson on May 16, 2018

Between 1992 and 2007, bone grafting was used in the treatment of almost two million patients in the United States.1 Bone grafts are used to facilitate the healing of complex bone trauma. This may be a multiple fracture or non-union of a long bone fracture, loss of bone due to disease, or surgical implantation of devices, like joint replacements, plates, or screws.

Bone grafting typically uses bone from another part of the patient’s body, such as ribs, hips, or pelvis, (an autograft) or bone harvested from a deceased donor or a cadaver that has been cleaned and stored in a tissue bank (an allograft).

Despite grafting markedly improving bone regeneration and clinical outcomes after severe bone injury or loss, there is still room for improvement. Researchers continue to investigate ways to enhance bone grafting techniques and provide faster and denser bone regeneration with lower morbidity.

One such development has been the use of bone graft substitutes, such as demineralized bone matrix, calcium phosphates, collagen- /hydroxyapatite-based substitutes, and bone morphogenetic proteins. Although autologous bone grafting was considered to be the preferred bone grafting modality,2 there is a trend towards favoring artificial bone grafts over autografts since they are readily available and obviate the need for additional surgery. However, bone graft substitutes can have limitations regarding strength under torsion.

Bioactive glass, by virtue of its biocompatibility, strength and range of achievable properties, has been widely used to facilitate bone repair and provide support in tissue engineering.3

Bone grafting is a surgical procedure that is beneficial for repairing bones that have been severely damaged by trauma and for replacing bone that is missing as a result of either trauma or disease. It can also be used to strengthen bone at the site of an implant, be that a joint replacement, screw or dental implant. The bone graft provides a framework to support and encourage the growth of new, living bone.

Autografts have long been considered the preferred means of bone grafting since they do not carry the risk of rejection. However, these necessitate additional surgery, which increases patient morbidity and the risk of infection. Furthermore, there may be issues with availability finding a suitable site to harvest bone of the needed shape and size.

Allografts obviate the need for additional incisions but carry the risk of immune response preventing the graft from being accepted. There is also still the potential for availability issues since the donated bone needs to be tissue matched with the patient.

A third option is not to rely on bone at all for the graft, but instead to use a man-made substitute. A range of different materials, including calcium phosphates, collagen, hydroxyapatite, have been investigated for use in bone grafting and are readily available. When using bone substitutes the nature of the materials must be carefully considered in terms of biocompatibility, resorption rate and strength.

The formation of new bone requires three key processes: osteogenesis (synthesis of new bone), osteoinduction (recruitment of stem cells and their differentiation into bone cells), and osteoconduction (the development of adequate blood supply to the new bone and correct structuring of the new bone cells). Bone graft substitutes are designed to facilitate and enhance these processes to promote rapid development of strong new bone.

Bone graft substitutes are frequently used to fill bone defects after orthopedic trauma. Ideally a synthetic bone graft substitute would have efficacy at least comparable to autograft, no immunogenicity, osteoinductive and osteoconductive properties, predictable resorption/degradation time, and no safety concerns.

Numerous studies have reported benefits of using synthetic bone substitutes for fracture treatment and spinal surgery.4,5,6,7 These include reduced pain, bleeding and healing time, and improved functional outcomes compared with autografts. However, there have been safety concerns and problems with unpredictable resorption rates with some of the bone substitute materials.8

Furthermore, the different bone substitute products have varying characteristics. They all only provide minimal structural integrity and none targets all three of the key bone formation processes.9 Although some bone substitutes closely mimic the structure of natural bone, they lack osteogenic and osteoinductive properties.

Bioactive glass has been successfully used in a range of tissue engineering procedures.3 With its versatility, achieved through the tailoring of properties through composition adjustments, its intrinsic strength and biocompatibility, bioactive glass was considered a prime candidate for improving synthetic bone substitutes.

Introduction of bioactive glass into the body induces specific biological activity that causes soluble ionic species to be released. These lead to the glass becoming coated with a substance similar to hydroxyapatite. The formation of this layer allows bioactive glass to bond firmly with both hard and soft tissues. Furthermore, bioactive glass can be manufactured to release nutrients required for bone regeneration.

It has been shown that damaged bone regained its original strength more quickly when repaired using composite combined with bioactive glass compared with bone repair using composite alone and that the efficacy achieved is comparable to that of autologous bone grafting.10,11

A recent study compared spine fusion in rabbits using a mineralized collagen bone substitute with and without added bioactive glass. The bioactive glass-collagen composite was shown to closely mirror repair by autograft in terms of the amount and quality of the new bone.12 In addition, fusion occurred earlier when the collagen composite was augmented with bioactive glass.13

Bone grafting is an important tool for the repair of damaged or disease bone. The gold standard is autografting, which uses bone harvested from the patient to avoid rejection reactions. However, the increased morbidity caused by the additional surgery needed to acquire bone for grafting has resulted in an on-going quest to find an alternative. Bone substitutes have shown efficacy, but do not promote the formation of new bone. Bioactive glass is biocompatible and enhances strong new bone creation. Studies have now shown that the addition of bioactive glass to bone substitutes can increase their efficacy and bone healing characteristics to rival those achieved with autografting.

Mo-Sci produces medical implant grade bioactive glass in a form suitable for mixing with bone composites and can tailor its composition to meet specific requirements.13

Posted Krista Grayson on Jan 5, 2018

Bioactive glass induces specific biological activity when implanted in the body that causes the glass to become covered with a substance similar to hydroxyapatite. The formation of this layer allows bioactive glass to bond firmly with both hard and soft tissues.

This behavior has instigated extensive research into the use of bioactive glass to facilitate the repair of damaged bone. Furthermore, these bioactive glasses are biocompatible, and so do not elicit immune responses that can lead to rejection of foreign materials introduced into the human body.

Although brittle, bioactive glass offers a strong, yet lightweight, biodegradable framework to support healing. Furthermore, new borate and borosilicate bioactive glasses have been shown to enhance bone regeneration. In addition, the composition of bioactive glass can be adjusted to determine how long it persists in the body before it degrades so it provides support as long as is needed.1

Considerable success has been achieved using bioactive glass in the repair of bone, soft tissue and cartilage.1 Bioactive glass has also been shown to be beneficial in periodontal reconstruction2 and to promote the healing of ulcers in patients at risk of leg amputation.3

The efficacy of bioactive glass in enhancing the healing of both hard and soft tissues led to investigation into their application in reconstructive surgery requiring the use of permanent implants. This article explores how bioactive glass can help encourage the integration of implants.

The human body has an amazing capacity to heal itself. However, in the case of multiple or complex fractures or serious infection or disease there can be too much of the original bone missing for it to heal satisfactorily. In such cases a bone graft or scaffold is required to support regeneration or bone fusion. Similarly implanted devices, such as plates, or screws and joint replacements, may be needed to reinforce or replace weak or damaged bones and joints. Similarly, implants may be required in dentistry to facilitate artificial replacement of a tooth root. These are usually in the form of a metallic screw positioned in the jaw bone that can support one or more false teeth.

Bone taken from another part of the patient’s body, an autograft, is the preferred implant for bone repair since it will not be at risk of rejection. However, this can be hampered by availability or suitability and incurs additional morbidity for the patient at the site from which the graft is harvested.

Titanium alloy implants have good biological compatibility but, in order for the implant to provide a strong structural support, it must be integrated into the bone (osseointegration) and it can take several months for the bone to grow in and/or around the implant. The implant must also be mechanically and morphologically compatible so it maintains good contact with the recipient bone to promote bony cell growth. In addition, there is the risk of metal implants being corroded by body fluids and releasing potentially toxic products.

Consequently, there has been much research into coatings for prosthetic metallic implants.4

Bioactive glass is one such coating material that is currently the focus of much research. Once in the body, an amorphous calcium phosphate layer forms on the surface of bioactive glass. Within hours, this layer incorporates blood proteins and collagen and crystallizes into hydroxycarbonate apatite. This layer is now very similar to natural bone mineral, and so bonds readily to the recipient tissues/bone. Bioactive glass is therefore a prime candidate for coating implants that need to become integrated into bone.

Including bioactive glass in polymeric scaffolding materials has been shown to accelerate the formation of a strong bond between the scaffold and tissue and promote healing.5 It followed that similar technologies may facilitate the osseointegration of the implants.

Numerous technical challenges have been overcome and titanium implants have been successfully coated with bioactive glass4 and evaluations of bioactive glass-coated implants have had promising results.6,7,8 Bioactive glass coatings on both orthopaedic and dental implants were shown not induce any adverse effects or inflammatory response in the surrounding tissue6. Furthermore, bioactive glass coatings accelerated cell attachment, spreading, proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization of the extracellular matrix and promoted rapid bone growth.6,7 In addition, the proportion of bone-to-implant contact were significantly greater for implants coated with bioactive glass.8

Bioactive glass can be obtained in a range of sizes and compositions9 suited to a range of applications. Indeed, bioactive glass can be custom made to specifications that precisely match a specific need, in terms of strength, degradation rate etc.

Implants are commonly needed in orthopaedic surgery to facilitate the repair of damaged or missing bone and in dental reconstructions. Although implants have been used with great success, procedures may be limited by rejection issues and toxicity concerns. Furthermore, it can take several months for an implant to become integrated into the recipient bone and this increases the risk of failure and prolongs recovery times.

The biocompatibility and strength of bioactive glass along with its ability to promote tissue regeneration has made it an invaluable tool in tissue engineering. With recent technological advances, it is now possible to coat metal implants with bioactive glass. Implants coated in this way have demonstrated great advantages in terms of both patient safety and recovery. The bioactive glass coating protects the metal implant from corrosion by bodily fluids thereby minimizing the risk of potentially toxic products entering the body. It also promotes new bone growth so the implant becomes secured in the bone more rapidly.

Bioactive glass coatings on implants can be used to encourage implant fixation, improve healing rates and maximize implant effectiveness.

Mo-Sci produce high quality bioactive glass in a form suitable for coating implants and can tailor its composition to meet specific requirements.

Posted Krista Grayson on Nov 15, 2018

Bone defects arising as a consequence of trauma or disease typically require surgical intervention to promote healing. The defect must be filled to provide a framework to support and encourage the growth of new, living bone.

The gold standard for filling bone defects is autologous bone, but the additional morbidity involved for the patient in harvesting bone for grafting has led to a growing preference for alternative methods. The need for further surgery to acquire the bone is eliminated by using donated bone, but such allografts carry the risk of an immune response preventing the graft from being accepted.

Learn more about calcium phosphate and other materials in our ebook, The Physician’s Guide to Synthetic Bone Grafting Biomaterials. Written by Mo-Sci CTO, Dr. Steve Jung.

Consequently, the use of synthetic bone graft materials is steadily gaining popularity.1 A variety of bone graft substitutes have been used in the search to find an alternative to bone that provides a rapid and strong repair. These include demineralized bone matrix, calcium phosphates, collagen- and hydroxyapatite-based substitutes, and bone morphogenetic proteins. This article will focus on calcium phosphate ceramics and bioactive glasses.

Calcium phosphate ceramics closely resemble the mineral components naturally present in bone tissue, and so represent an attractive option for a synthetic bone filling material. Their biocompatibility and ready availability have led to calcium phosphate ceramics being widely used as an alternative to autografts and allografts.

Calcium phosphates have proven to result in good cell attachment when used as bone substitutes and tissue engineering scaffolds. They are also known to provide predictable outcomes and lower morbidity for the patient whilst being cost effective compared with traditional bone grafts.2,3

Initially, calcium phosphate ceramics lacked sufficient porosity to allow immediate bone ingrowth and rapid integration into the bone tissue. However, variations in the parameters used during the preparation of calcium phosphates has led to the production of products with more favorable chemical and physical characteristics, such as specific surface areas and porosity.

Careful selection of the precise combination of properties has enabled development of bone filling materials that improve the adhesion, proliferation and differentiation of cells, thereby allowing improved osteoconductivity.4

Bioactive glass is a particularly favorable form of synthetic bonegraft as it is osteoconductive, bioactive and antimicrobial. In addition, minerals, such as calcium, are released from the bioactive glass providing key substrates for the production of new bone.

Bioactive glass induces specific biological activity when implanted in the body that causes an amorphous calcium phosphate layer to develop on its surface. Over a few hours, this layer incorporates blood proteins and collagen and crystallizes into hydroxycarbonate apatite, which makes it very similar to natural bone mineral. Bioactive glass thus bonds readily to the recipient bone.

Furthermore, the properties of bioactive glass, such as particle size and rate of reabsorption, can be tailored by adjusting the exact composition to meet the requirements of a specific repair procedure.4,5

Bioactive glass has been successfully used in a range of tissue engineering procedures.3 With its versatility, achieved through the tailoring of properties, its intrinsic strength and biocompatibility, bioactive glass presents many of the features needed in a synthetic bone substitute.

Bioactive glass bone filler composites have also been loaded with drugs, proteins and growth factors to facilitate repair by delivering the therapeutic agents directly into the defect region.7

It has been shown that damaged bone regained its original strength more quickly when repaired using a composite bone filler material that included bioactive glass compared with bone repair using composite alone. Furthermore, when bioactive glass is added to the bone substitute, the efficacy achieved is comparable to that obtain with the gold standard—autologous bone grafting. A bioactive glass synthetic bone substitute was recently shown to be effective in the repair of cavitary bone defects in patients with chronic osteomyelitis.8

Bioactive glass has also shown great promise in a variety of other orthopedic applications including spinal fusion and the coating of implants and the strengthening of bone at the site of joint replacements, plates, or screws. Bioactive glass coatings on orthopedic implants did not induce any adverse effects or inflammatory response in the surrounding tissue.9 Furthermore, bioactive glass coatings accelerated cell attachment, spreading, proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization of the extracellular matrix and promoted rapid bone growth. Spine fusion performed in rabbits using a mineralized collagen bone substitute with and without added bioactive glass demonstrated that the addition of bioactive glass led to earlier fusion of the bone. In addition, the addition of bioactive glass achieved a repair very similar to that seen with autograft in terms of the amount and quality of the new bone.10

Mo-Sci produce implant grade bioactive glass in a variety of forms suitable for a range of bone repair applications, and can tailor its composition to meet specific requirements.5 The composition and form of the bioactive glass can be adjusted to match the intrinsic conditions of the patient and the rate and pattern of bone formation required.4